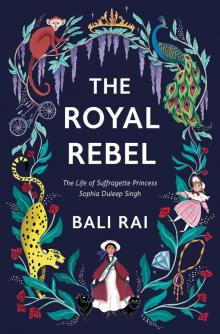

The Royal Rebel Read online

Huge thanks to Ailsa Bathgate

and Catherine Coe for helping to turn a

good idea into a great story. And to

Rachael Dean for the wonderful artwork.

CONTENTS

Title Page

Acknowledgements

PART 1: England 1884–1893

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

PART 2: India 1903

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

PART 3: England 1903–1928

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Copyright

PART 1

England

1884–1893

CHAPTER 1

I watched as a grumpy baboon stole a silver teapot from a garden table. She refused to give it back and bounced around the lawns, holding the teapot and shrieking. One of the servants tried to wrestle the teapot away, but our baboon didn’t let him. She turned her back, showing her pink bottom, and began to bang the teapot against her head.

“GIVE IT BACK!” the servant cried.

The baboon growled and ran off towards some trees. A tall, unfriendly ostrich watched the baboon for a moment. In the trees, blue and red parrots squawked and chattered. My younger brother, Eddie, squealed with delight.

“Please don’t worry,” I said to our servant. “It’s not your fault.”

The servant nodded and walked back into the house. Five-year-old Eddie took my hand.

“I want the monkey,” Eddie said. “Can we play with the monkey?”

I was eight years old but wise enough to correct Eddie.

“Baboons are apes, not monkeys,” I told him. “Monkeys have tails; apes don’t.”

“I want to play with the monkey!” said Eddie.

Luckily for him, we had monkeys too.

Our home, Elveden Hall in Suffolk, was huge. My father, Maharajah Duleep Singh, had turned it into an Indian palace. Every room was crammed with ornaments and furnishings from his homeland. The gardens were planted with rare plants, and exotic animals lived in the grounds surrounding the house. We had eagles and vultures, monkeys and ostriches, and many expensive parrots. And our bad-tempered baboon. For us children, it was often a paradise. Often, but not always. I sometimes felt as if there was a grey cloud lurking beyond the blue skies.

Two days after the baboon stole the teapot, I found Eddie crying at the foot of the main staircase. He was calling for Mother, but she was nowhere to be found. Mother had withdrawn to her bedroom and locked the door. Not for the first time.

“Shush now, Eddie,” I said. “I’m here.”

He ran into my arms and sobbed a bit longer.

“Come on,” I said. “Let’s go and find a book to read.”

Eddie and I sat on a purple velvet sofa in one of the drawing rooms. The walls were lined with paintings from India. The floor space was filled with wooden carvings of elephants, tigers and other animals.

“Where did the picture go?” asked Eddie.

He pointed to a space on the wall.

“Oh,” I said.

The missing painting was of our grandfather, Maharajah Ranjit Singh. He had been the ruler of the Sikh empire and was a hero to Indians. He had fought the British and won when they tried to invade, and he built a kingdom in India that no one could challenge.

Maharajah Ranjit Singh was wise and strong, and fair to all people. His empire was based around the Punjab region of Northern India – the home of our ancestors, according to Father. It was a land of rich, fertile soil, flat plains and five rivers. Punjabi people were proud and fierce, and utterly loyal to our family. Our grandfather was the reason Eddie and I and our other siblings were princes and princesses.

“That was one of my favourite paintings,” I told Eddie.

A few things had vanished from the house recently, which I found confusing. Later that evening, I asked my older sisters about it.

“Father’s selling everything,” Catherine told me.

Father spent hardly any time with us. Mostly, he was in London on business. When he did come home, Father always locked himself away, or became angry and irritable. But I still adored him.

“Why is he selling things?” I asked.

“Oh, you silly little thing,” said Bamba. “It’s obvious.”

“Not to me,” I told Bamba.

“Father has spent too much money,” Catherine explained. “On this house and the animals, and on his business affairs …”

“He’s bankrupt,” Bamba added. “He’s brought us so much shame!”

I did not know what bankrupt meant, but it was easy to guess. Father was short of money, and his only option was to sell things. Both of my sisters looked annoyed, but I didn’t know why.

“Father’s trying to help us,” I said. “We should be grateful.”

A servant placed our dinners on the table before us, and Bamba pulled a face.

“Father is the reason we’re in this mess,” she said.

“Don’t worry,” said Catherine. “One day, you’ll see …”

I turned away, annoyed they were speaking to me like a little child, and I made sure Eddie was using his knife and fork properly.

CHAPTER 2

The following morning, I sat in the gardens, watching a troop of small brown monkeys running about the lawns. I was trying to read but found it hard to focus. It wasn’t the animals that were distracting me – I was used to them. I was thinking about Mother and how she hid away in her room all the time. My elder brothers, Victor and Freddie, had moved away to boarding school, and I missed them. I≈could have done with Freddie’s advice, but I rarely saw him. And my sisters were always busy.

“Miss?” I heard a young servant say.

“Yes?” I replied.

“Prince Eddie is asking after your mother again,” the servant told me. “He seems rather upset.”

“Thank you,” I told her.

I set my book aside and went to find Eddie. He was sitting at the top of the grand staircase, and he looked glum. Above us, a rare and expensive chandelier hung from gold chains attached to the ceiling.

“I’ve been knocking on Mother’s door, but she isn’t answering,” Eddie said. “I want Mother.”

I gave him a hug.

“Shall we see if there are any sweets in the kitchen?” I asked. “Or some fruit?”

Eddie nodded and wiped his eyes.

“Why isn’t Mother answering?” he asked.

“I don’t know,” I replied. “Perhaps she feels unwell. I’ll ask her.”

I left Eddie to chomp on sweets, went up to Mother’s bedchamber and knocked on her door.

“Leave it to one side,” she said, assuming I was a servant with a food tray. She had a strong Arabic accent, from being raised in Egypt. “Whatever it is.”

“It’s me, Mother,” I replied.

“I’m busy,” she told me.

“Mother, I’m worried about you.”

There was a long pause.

“There’s no need,” she told me at last. “I am perfectly fine.”

“Will you be at lunch then?” I added.

“Dear Lord!” Mother yelled. “Leave me be!”

When I returned to the kitchen, I was as glum as Eddie had been. I would have stayed glum too, but the grumpy baboon had other plans.

“Stop that animal!” I heard a male servant shout.

The baboon came tearing into the kitchen, jumped onto the table and sent dishes scattering. In her mouth was a silver wine goblet. The servant followed, his face pink from running and his

expression one of shock and anger. The baboon squealed, as if daring the servant to catch her. She bared her bottom once again, climbed to an open window and disappeared.

“Blasted beast!” the servant yelled.

Eddie burst into a fit of laughter. His eyes streamed, and he clapped with delight.

“Monkey! Monkey!” he shrieked.

I smiled and took a boiled sweet from the jar in front of him.

Two days later, Father was home. I found him sitting alone in the dining room after supper. Father’s visits to Elveden were so rare, I was shocked to see him.

“Father?” I said.

He raised his head from some papers scattered across the table. He was nearly bald, and large around the middle, with dark skin and eyes. He had a moustache that grew down his face and into a beard. His remaining hair was greying and wispy, and he seemed exhausted.

“Saff!” Father said, using my pet name as he beamed.

He gave me a huge hug and sat me down on his knee.

“You know, your grandmother would have been delighted by you,” Father said.

My grandmother was called Rani Jindan. Rani meant “Queen”. Alongside my grandfather, she had been a true Punjabi hero. She was just as loved and remembered by Indians as he.

“She was a great woman,” I replied.

Father nodded.

“She was,” he said. “And cruelly taken from me, just like my kingdom.”

When my grandfather had died, the Sikh empire fell apart. Eventually my father had become Maharajah at just five years old. His mother had ruled with him, until the British took Father away and stole his kingdom. That was why we lived in England, and also why Queen Victoria became my godmother. It was an awful, sad story, and Father wiped away tears as he remembered his mother.

I changed the subject.

“Are you home to stay?” I asked.

“No,” Father said. “I have very important work to do in London.”

I smiled because I felt nervous.

“Mother is unwell,” I told him. “She hasn’t left her room.”

“Hmm?” Father said, his attention taken by his papers.

“Mother,” I repeated.

“Yes, yes,” he said, brushing off my concerns. “I’ll go and see her before I leave. It’s nothing, Saff. She’ll soon be herself again.”

Father tapped a letter he’d been writing.

“I’m writing to Her Majesty,” he told me. “She will help me. She has a duty to our family. A debt that she owes us …”

My godmother, Queen Victoria, had always been a close friend to Father. I wondered what debt she owed us but didn’t ask. Instead, I went to bed. When I awoke, Father had already left for his house in London.

CHAPTER 3

As Mother continued to hide in her room, I spent my time out in the grounds of Elveden. I explored on a small pony – a present from Father when I was younger. I also began to spend time at the kennels, which were always busy with dogs. It kept me away from the problems at home.

Over the next two years, Father grew increasingly distant and sold more of our belongings. He even arranged an auction for our most valuable things – embroideries, carpets and rugs, jewels and silverware. If the angry baboon didn’t steal the silver, Father sold it.

Mother stayed in her room, so my sisters and I had to look out for ourselves, and for Eddie, who was now seven.

“Eddie needs a tutor,” Catherine said one afternoon. “His education will suffer otherwise.”

The four of us were sitting in a drawing room, the one with the plush velvet sofa. Several more paintings and wooden carvings had gone. The room was my favourite, but it had begun to feel colder and less like home. The same was true of Elveden itself.

“I wonder what Father will do next,” Bamba said. “This place is falling apart.”

“Have you seen how many rabbits there are?” I asked.

Father loved hunting on our vast estate. During better times, he had invited his friends to hunt with him, including the Prince of Wales. Father had always been Queen Victoria’s favourite – ever since arriving in England as a child. He had grown up alongside the Queen’s children and had been a regular at her court. The Queen loved Father and had ensured our family was well looked after. But things were changing because of Father’s financial troubles. Now, hardly anyone visited, and the rabbits could roam without fear of being hunted.

“The grounds are overgrown too,” Bamba replied.

“Well, we have no gardeners any more to keep them tidy,” Catherine told her. “The estate is in ruins.”

“I wish Victor and Freddie were here,” I said.

“Well, we do have each other,” said Bamba.

As she said that, Eddie climbed onto my lap, resting his head against my chest.

“That’s true,” I said.

But Elveden was the only home I had ever known. Watching it fall into ruin broke my heart. It didn’t feel like home any more. Then Father came up with his most foolish plan yet.

He arrived one evening, tired and irritable, and ate supper alone. Then he told us children to gather together in the drawing room.

“I have some wonderful news!” Father said. “I will be along shortly.”

As we waited, Bamba groaned.

“I wonder what wild scheme he’s come up with now?” she asked.

“Hear him out first,” Catherine told Bamba.

Eddie was tired. He curled up on the purple sofa, which was the last piece of furniture left in the room. It was once a warm and safe place, but no longer. Yet I was still excited. What had Father got in store for us? I wondered.

“Perhaps he’s decided to come home for good?” I said.

“Yes,” replied Bamba. “And he’s bringing a flying elephant with him …”

“Bamba!” said Catherine. “That’s not fair.”

“None of this is fair,” said Bamba. “We didn’t choose any of this.”

“Father is doing his best,” I said.

Both of my sisters groaned. Father appeared just then, holding a crystal glass filled with whisky.

“Children!” he boomed. “How very good of you to attend …”

Father eyed the almost bare room and sighed.

“I have made a decision about our future,” he added.

“Have you?” asked Bamba. “Does Mother know?”

“Mother is resting,” Father replied. “I wanted to tell you children first.”

Eddie got up and went to Father with his arms outstretched.

“No, no, boy,” said Father, turning Eddie away. “You must learn to control your emotions. You are a prince, and heir to a kingdom.”

Eddie wailed and ran to me. I hugged him close and stroked his long hair. I knew that Father loved Eddie – he loved us all. Yet I was sad that he had not embraced Eddie.

“I have booked a trip for us,” said Father.

“Why?” asked Catherine. “I thought we had no money?”

Father snorted.

“That is none of your concern, my dear,” he said. “You must trust in your father.”

“Where are we going?” asked Bamba.

“All will be revealed soon,” said Father. “I am making the arrangements and soon we will leave.”

“Leave?” I asked. “We’re leaving Elveden?”

Father smiled.

“For a little while, yes,” he said.

“But I don’t want to leave our home,” I replied.

“Hush, child,” Father said. “I will reveal more soon.”

He stood, finished his drink and left, muttering under his breath.

“I don’t want to leave,” I said again.

But I had no choice. Father had booked us a trip to India, via Egypt. As our departure drew nearer, Elveden was almost emptied of our belongings. I felt miserable walking down the main staircase on our last morning.

“Hurry now, children!” said Father. “We have no time to waste!”

The serv

ants had carried our cases to a waiting car. Another car sat behind it with my sisters already inside, glum and angry.

“When we come back,” said Eddie at my side, “I’m going to ask for a swing in the gardens. A slide too …”

“Hush now,” I heard Mother tell Eddie from the landing. “Let us focus on what is to come.”

Mother had tied her hair into a tight bun and wore a black dress and shoes. Her skin was the colour of dark oak and looked dry. Her once shiny complexion was gone. I had always loved Mother’s skin. It seemed to glow with light before she began drinking too much. Now it was lined and made her look ill.

Yet I was so pleased to see Mother up and about that I didn’t care what she looked like. Recently she’d begun to take part in daily life again, after learning about our trip. It was very welcome, especially with Father so occupied.

“Will you be pleased to go back to Egypt?” I asked Mother when she joined us at the foot of the stairs.

Mother had been raised in Egypt, by Christian missionaries. I wondered if she ever missed it.

“I’ve always wanted to return,” she told me. “But I’d rather stay here.”

“Me too,” I told her.

Mother glanced at the dusty walls, stripped of their paintings, and the empty hook from which the chandelier had hung. Elveden was lost – only the shell of the house remained. Everything that made it home was gone or about to leave. I watched Eddie run out to the cars before I spoke again.

“We won’t ever return home, will we?” I said at last. “Father has sold Elveden.”

Mother took me in her arms and I almost cried.

“Oh, Saff,” she said, “home is not a building. Home is a feeling …”

She kissed my head.

“As long as we are together, we will be at home,” Mother added. “Come along, no time for tears.”

She led me to the car. My heart was breaking and I felt sick, but I did not look back. My time at Elveden was over. I would never truly be at home ever again.

CHAPTER 4

The Royal Rebel

The Royal Rebel Mohinder's War

Mohinder's War Starting Eleven

Starting Eleven Glory!

Glory! (Un)arranged Marriage

(Un)arranged Marriage Tales from India

Tales from India The Night Run

The Night Run Voices: Now or Never

Voices: Now or Never Rani and Sukh

Rani and Sukh Stars!

Stars! Web of Darkness

Web of Darkness The Crew

The Crew Fire City

Fire City The Last Taboo

The Last Taboo