Voices: Now or Never Read online

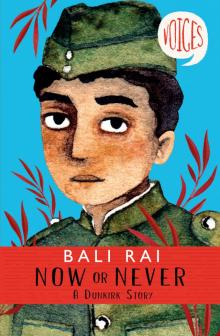

NOW OR NEVER

I would like to thank Mark Ashdown and his siblings for the valuable insight into their father’s service during World War Two.

I’d also like to thank Tony Bradman and the team at Scholastic for asking me to take part in this wonderful and much-needed series. Bali Rai

NOW OR

NEVER

BALI RAI

Series Consultant:

Tony Bradman

CONTENTS

Cover

Dedication

Prologue

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Chapter 22

Chapter 23

Chapter 24

Chapter 25

Epilogue

Author Note

Copyright

PROLOGUE

It was still dark when I left my village, carrying only what I needed to travel. My family were fast asleep, and I did not wake them. I was running away, desperate to find my fortune, desperate to follow in my grandfather’s footsteps. My decision was swift, but the planning took some months. Now, I was finally ready to leave. And even though my heart ached at the thought of my mother’s distress and the tears of my younger sisters, I did not waver. My grandfather had taught me to believe in myself, and to be sure in my actions. Now that I was going, and he was no longer with me, I wondered what he might think. Whether he was looking down on me as I sneaked away.

I stopped a mile from the village, which would soon be consumed by the city of Rawalpindi and become another of its many districts. I stood by a grove of trees, under which my grandfather, my baba, had often sat. There, he would take shade from the sun, chatting with his friend Mr Singh, playing cards. There, he taught me many lessons about life and told stories of his time in Europe, fighting in what they had called the Great War.

Now, as I stood and thought of him awhile, I was leaving to have my own adventures, hoping to follow Baba’s example and become a man. I had no idea what awaited me, and I will admit to some fear. Mostly, however, I was excited. Baba had no gravestone to mark his passing. Instead, I touched his favourite wooden seat, under his favourite tree, and asked for his blessing.

Then, without another rearward glance, I set off on my journey…

1

We disembarked in 1939, during the coldest winter for a hundred years, many thousands of miles from home. As Company 32, of the Royal Indian Army Service Corps, we had been ordered to Europe alongside three other units. They called us Force K-6 and we were sixteen hundred men and close to two thousand mules strong, with a few horses in addition. Our British rulers had made a terrible mistake when the war began, ignoring animal corps, and relying solely on vehicles for transport. Only, when the British Expeditionary Force reached France, they found themselves bogged down by muddy and then frozen roads and lanes and fields, unable to get supplies to the front lines quickly enough. That became our job.

On our arrival, everything was covered in snow and ice – the houses, the streets, the fields. The locals shivered as they passed us by, hidden under thick layers of clothing, with moth-eaten blankets wrapped around them. The rivers and streams were frozen, and the bows of every tree weighed down by ice and snow. Every scene seemed leeched of colour and joy and warmth, as though the whole country lay under some great depression beyond the war. I came from Rawalpindi, in the far north of India, and was used to the cold, but this was something else. It chilled my bones, and set my teeth chattering. Occasionally, the biting winds even made conversation difficult, so badly did my jaws vibrate. But at least I had a voice to find.

Our mules were silent. Always silent. They had been gagged; their vocal cords surgically altered before we embarked on the long journey from India to Marseille, in France.

“That should stop them alerting the enemy,” a fellow soldier had said.

Yet, I could not bring myself to approve of such barbarism. I was very young and had little experience of cruelty. But, when we reached France, I witnessed the horror and savagery of war firsthand. Cruelty lingered everywhere in conflict. A nasty business and no mistake.

When we docked at Marseille, I had grown excited by the prospect of a foreign land. Barely eighteen according to my forged documents, in reality I was just past my fifteenth birthday. I had lied to enlist and run away from home, desperate to emulate my late grandfather, who had fought during the Great War and told tales of bravery and camaraderie, honour and duty. I looked older than my years, but at heart I was still a boy. A boy who wanted to become a man.

I knew my actions would hurt my family and cause them sorrow, but I enlisted regardless. The pull of my dreams was much too strong. I did not even stop to think. Looking back, I was immature and selfish, and yet I felt great pride too. I joined many others from my city, as we trained under the British some distance from my home. We were attached to an animal unit, specifically mules, and taught to care for our charges. To understand our vital role in supplying combat units with ammunition and food, and whatever else they required during battle. In India, we saw little action. Then, very quickly after I enlisted, the call came to join the war in Europe. Soon everything changed.

The French people were not particularly welcoming, but they did not trouble us either. Most were too busy trying to keep warm and too frightened of what lay ahead. The same lack of cordiality was true of our British comrades, which I found harder to take. Surely, we were all brothers in arms, fighting the same fight? However, it was wartime, and there was no use in dwelling on such things. Besides our Captain, John Ashdown, made sure we were looked after.

“We are here to do a job,” he’d tell us. “As important as any other. Remember that.”

After disembarking ourselves and our animals, we were sent to a transit camp outside Marseille, and from there we headed north. Soon each company was sent to different postings. We moved around a great deal, becoming skilled in erecting tents at each new camp. Often, we tethered the mules under trees, or tied them to buildings, covering them in blankets as protection from the cold and retreating to our shelters. Despite the freezing temperatures, we tried to warm ourselves with tea and hardtack biscuits, and some tinned bully beef. It was far from ideal, but it was all we had.

During my first month, I was weary and cold, and uncertain of why I’d chosen to join up. I had dreamt of grand buildings, exotic food and friendly folk, but all I saw of that great country was fields and trees and mud and snow. Rawalpindi was chaotic and haphazard, warm and inviting. The France I first encountered was none of these things. My closest comrade, Mushtaq Ahmad, grew annoyed when I said as much aloud.

“What did you think we would find, brother?” Mush asked me. “We are at war.”

“I just expected more” I replied.

“More?” asked Mush. “We are just Indians. These people do not think of us as equals. This is not our war, Faz.”

Mush shook his head. He was paler than me, with green eyes and a hooked nose. His jet-black moustache swept around his mouth and was curled at the ends.

“It is our duty, Mush,” I replied. “You know this.”

We Indian soldiers had a motto, a rallying cry for when things were going awry. If anyone in India questioned our loyalty to the British, we would simply say “Hukum Hai�

�� – it is our duty. Now, I reminded Mush of that duty.

“Duty?” he replied. “I am here because I had nothing, and the British pay us. I was a peasant farmer at home, without even a field to call my own. My duty is to you and the rest of our brothers. I do not care about kings and empires.”

“Look,” I added, picking up a tin cup full of tea. “We are cold and tired, and in a foreign land. But we have a task to perform, and inshallah, we will not shirk it. We do not run from hard work.”

“I know this,” he replied. “But there is nothing more than this, Fazal.”

“I just thought…” I began

“You thought you might find a nice French girl to take home?” he joked. “I’m sure we will meet a few blind ones.”

“Idiot,” I said with a grin.

“Buffoon,” he replied.

Eventually I settled into a routine. Upon waking and washing, and after a breakfast of canned meat, hard bread and tea, I would groom the mules alongside my comrades. This involved checking them for signs of illness or infection and brushing their coats. Then we would check their hooves for stones and other detritus, removing anything we found with spiked hoof picks. Occasionally, the veterinary officers would ask about the mules’ welfare, and I would be asked to translate.

“You’ve a good grasp of the language, Khan,” Sergeant Buckingham said one morning.

“Yes, sir,” I replied. “My school followed a British curriculum.”

“You come from a well-to-do family then?” said Sergeant Buckingham.

“Not so well-to-do,” I told him. “But we have decent enough lives. My father works as a court administrator and my grandfather fought during the Great War.”

“My father too,” he replied, his expression darkening. “Died at The Somme. I never really knew him.”

“I am sorry,” I said. “My condolences.”

“It’s fine, Private Khan,” said Sergeant Buckingham. “Each of us has made sacrifices for the Empire. Now, any problems with the animals?”

“No, sir.”

“Good, good,” he replied. “Saves me a blasted job. I’m off to get a cup of chai. Carry on!”

As he sauntered away, I saluted and got back to my task. The mules stood with their heads bowed, many of them feeding from cloth bags tied around their necks. My next job was to weigh out a serving of oats for their feed, and I called to Mush.

“Scales,” I said.

Mush nodded and brought them across.

“Feeling better today?” I asked.

“Yes, brother,” he replied. “Hukum Hai…”

2

We moved around France until May 1940, before a change of fortune sent us headlong into a nightmare. Captain Ashdown gathered us one morning and broke the news, at a temporary camp in a small town between Lens and Lille.

“It seems that Hitler has decided to invade Belgium,” he told us.

Murmurs of anxiety spread through the men, but the Captain hushed them with a cough. He was tall, with a neatly trimmed moustache, and wore spectacles under his peaked hat. His khaki uniform was immaculate, as always, and his black leather boots shone. Captain Ashdown loved my country, was fluent in Punjabi and Urdu, and always respectful of we Indians. It made him all the more admirable

“German troops have marched into Belgium, via The Netherlands and Luxembourg. So, naturally our combat units have been sent to block the enemy advance.”

A cheer went up amongst the men, and Captain Ashdown smiled before holding up his right hand.

“However,” he added, “the Germans are trying to outflank us. They’re advancing through the Ardennes Forest, just north of the Maginot Line.”

The man next to me gasped. Mush leant over and whispered.

“I thought this Maginot could not be broken?”

I shrugged.

“That is what they said,” I replied.

If the Germans managed to cross the Maginot Line of defence, they would cut us off from Allied troops in the North. That would be catastrophic. Captain Ashdown waited a moment, letting the news sink in.

“Therefore,” he said, “and with utmost haste, we must move north. We cannot let the Germans outwit us. We leave in two hours.”

As he strode away, the men around me spoke in hushed and fearful tones. So far, we had seen no combat. Sergeant Buckingham had called it the Phoney War, parroting British newspapers. Now the real war was upon us. “Hurry up!” the Sergeant yelled. “You heard the Captain. Jaldi!”

I rushed to gather my meagre belongings and then went to help prepare and tether the mules. In the end, I was given three animals to guide, and within the hour, we were ready to march. Two of my mules had dark, nut-brown hides and sturdy hindquarters. The third was slightly smaller, with pale brown hide the colour of my grandfather’s eyes, and white patches on its legs. All three had white snouts and the elongated ears of their donkey fathers.

“Perhaps I will call you Baba,” I told the smaller mule, using the Punjabi word for granddad. “And, perhaps I can tell you what I cannot tell him?”

The other two raised their heads, as though they understood and were envious.

“I won’t forget you either,” I said to them. “You can be my sisters, although you do smell better…”

I laughed at my own joke and saw Mush shaking his head.

“You utter clown!” He laughed.

All around us, across the makeshift base, every unit was on the move. It seemed as though the entire Allied Force was preparing to leave.

“Will no men stay on here?” I asked Mush.

“Perhaps some French troops,” he told me. “Besides, if we cannot stop the Germans, the war will be over by September. And not in our favour.”

By the deadline, we were on the move. The combat units had trucks and other vehicles, as did the officers. We muleteers marched in convoy, leading our animals behind us. As we left the makeshift base, scared and angry locals accosted us, many seeming to curse us in French. About a mile north, as we marched through a village, some local women ran towards us. One of them, similar in age to my mother, took hold of my free hand and implored in French. But I had no idea what she was saying, and I simply shook my head.

It felt wrong to be leaving the people undefended, but our need was great and time short. The thought of our troops surrounded by the Germans was too much to bear. We had come to France to win the war, not lose it in the first genuine skirmish. Should the worst happen, the shame and dishonour would haunt us forever. After running away, I could not return to face my family after such humiliation, and nor could my comrades. It was the second harsh lesson that war taught me.

The journey took us through some breathtakingly beautiful scenery. I was much taken by France’s forests and rivers and hills and fields. My grandfather had longed to return to the West, but age and illness, and finally death had made that impossible. Now, I wished he were with me. Wished that I could write him a letter, even. Perhaps, I thought, I might compose one anyway, as soon as we find time to rest. It did not matter that he would never read it. Just that I wrote down my thoughts and expressed my feelings.

Only, rest was but a fanciful dream. We did not really rest. We merely stopped and struggled to regain our strength, before leaving again, wearier than ever. We did not even have time to pray, and this upset many of my comrades. It was another sacrifice for King and Empire, and it bothered me greatly.

“Why no trucks for us?” one man asked. “Surely we would move faster that way?”

I shrugged.

“It is our lot,” I told him. “Our duty.”

“Pah!” he replied. “Forget duty. This is about our worth. We are not important enough.”

I turned away, and ignored him, but I could not disregard his words. The further we travelled, and the wearier I became, the more I realised he was correct. To the British, we seemed as worthy as our mules. Not all of the British, of course. Captain Ashdown made sure to check on our welfare throughout the trek, but nonet

heless, my feelings remained. And just like my mules, I felt voiceless too.

Soon things grew more serious. We began to encounter panicked French locals and bomb-damaged vehicles, roads and buildings. On two occasions, we passed by dead bodies left to rot in ditches. Rumours of German fighter planes spread amongst us, and we quickly realised how difficult our situation had become. Scores of locals had joined us, carrying what little they could. I saw frail and elderly people being escorted, and mothers carrying babies. The locals fled on pushbikes and horse-drawn carts, and everywhere we went, we began to find burnt-out Allied vehicles and defences.

“We’re destroying anything we can’t carry,” Sergeant Buckingham told me during a brief respite. “We’ll be doomed if the Germans attack us with our own weapons.”

I was checking Baba’s hooves when the Sergeant approached. He looked a little drunk.

“But won’t we need weapons to fight back?” I asked.

The Sergeant smirked.

“I’m not sure we will fight back,” he told me. “Certainly not in the near future. This looks like a retreat, Khan. Hitler’s outsmarted the toffs back at home, I’d say. It’s a mess, all of this.”

Some hours later, we stopped in woodland and drew breath. Baba and my sisters seemed agitated so, despite my desire to sleep, I tried to calm them. If you have never seen a voiceless mule bray, I pray that you never will. Baba turned his head towards me and as he tried to cry out, his head shook, and his jaw snapped open and shut. I rubbed his head and back, and whispered kind words, but he did not calm down. Soon, the others followed, as though I’d entered some nightmare. The sight of them caused me great sadness.

“Mine have done the same thing,” Mush told me. “They are agitated and scared, just like us.”

I shook my head.

“They cannot speak,” I told him. “So, they are less fortunate than us. If I am scared, I can speak to you. We have taken that from these beasts. It is an indignity, brother. It is cruel.”

“Like the Empire took from us,” said Mush, and I raised an eyebrow.

The Royal Rebel

The Royal Rebel Mohinder's War

Mohinder's War Starting Eleven

Starting Eleven Glory!

Glory! (Un)arranged Marriage

(Un)arranged Marriage Tales from India

Tales from India The Night Run

The Night Run Voices: Now or Never

Voices: Now or Never Rani and Sukh

Rani and Sukh Stars!

Stars! Web of Darkness

Web of Darkness The Crew

The Crew Fire City

Fire City The Last Taboo

The Last Taboo