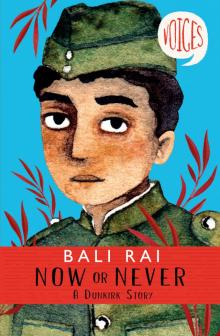

Voices: Now or Never Read online

Page 2

“But what of duty?” I asked him.

“Duty and honour are not the same things,” he replied. “There is no honour in this Empire. Yet, I have sworn upon my own honour to fight, and I will do that. But with my eyes open.”

“Eyes open?” I asked, unsure of what he meant.

“Yes, brother,” he explained. “I know what I am fighting for, and I am a man of my word. But being honourable does not prevent us from being honest, too. Truth is a parent of honour.”

I sat and took some hardtack from my bag and crunched on it.

“And what is the truth?” I asked Mush.

“Simple,” he said. “We are beasts of burden, leading beasts of burden, for King and Empire. We chose this life, even though the Empire thinks so little of us. We took on this duty, and we cannot shirk it.”

“So, we must simply endure?” I asked.

“Yes,” Mush told me. “We have no other choice. I must survive, for the sake of my wife and children. I cannot fail them.”

I thought of my home village, my mother and my family. I thought of the pretty girls who walked down the lanes around my house, the fat mangoes that were so prized in the summer, and the fields of wheat and corn that seemingly stretched on for days, bathed in glorious sunshine. I thought of spiced and fried onions, and thick dal with corn roti, and the sweet and creamy texture of rassa malai, my favourite dessert of curds in sugary milk.

“We had a choice,” I eventually said to Mush. “We could have stayed at home.”

“Home?” he replied. “We are very far from home, brother. Not even these mules, these little ships that carry us forward, can take us home. Until we have served our purpose, this is home.”

I sighed and closed my eyes and longed for some real sleep. That when I heard the Stuka’s dreadful siren…

3

In Rawalpindi, we have hornets the length of a man’s middle finger. They are yellow and green, and orange and black, and should they swarm, you would not escape with your life. That is what the German aircraft, the Stukas, came to remind me of, and they were even deadlier.

I heard its engine first, a distant droning sound. But as it drew near, another sound made my legs shake. It was an incessant whining, like Death warning us to take refuge.

“ENEMY PLANE!” I heard Sergeant Buckingham holler. “GET TO COVER!”

I grabbed hold of my animals’ reins and led them deeper into the trees. Mules are perfect creatures for war. They are resilient and agile and can go where vehicles cannot. But as they stepped over fallen logs and trudged through thick, brown mud, they seemed to sense the alarm. My lead mule suddenly stopped, causing the others to follow suit.

“Come on, Baba!” I urged, pulling on the rope, but he refused to budge.

“If you do not hide, Baba, we will die,” I warned.

The fighter was closing in and its machine guns began to clatter. All around us, the bullets stripped away chunks of bark. My comrades yelled and screamed in panic and hid in the bushes and undergrowth. The mules panicked too, and some of the men tried to calm them. I could not leave my animals alone, so I hid behind them, and awaited my fate.

But the Stuka dropped its bombs closer to the road, and the explosions merely shook the ground beneath me. I heard more screaming, and shouting, and then it was gone, leaving us shocked and deafened, and frightened to our cores. As we gathered ourselves, I saw Captain Ashdown rushing towards us.

“Khan!” he yelled when he spotted me. “Civilian casualties on the road. We need to help them. Now!”

Two of the medics came with me, and when we reached the road, we saw absolute carnage. The bombs had hit a cart and blown a hollow into the road. On either side lay destroyed trucks and jeeps, and human bodies, too. There was nothing to be done for the dead, but many of the wounded were beyond help too. It was more than I could bear, and I threw up. Mush appeared at my side, his arm on my back.

“We must help,” he told me. “Even those who are dying.”

I retched and retched, until the heaving subsided, and then I tried to control my breathing.

“COME ON!” I heard Sergeant Buckingham yell. “MOVE YOURSELVES!”

We spent an age trying to help the survivors, and longer still removing the dead. A company of white soldiers joined us, and I was left with a Private Sid Smith.

“We’re in some trouble, here,” he told me.

His hair was curly and ginger, and his pale skin freckled.

“Why must we run?” I asked. “Why don’t we turn and fight?”

Private Smith shook his head.

“The Germans outnumber us,” he replied. “I’ve heard perhaps two to one. And they’ve got more vehicles and weapons. I don’t know who planned this expedition, but they want shooting.”

I nodded and continued with my awful task. By nightfall, we were exhausted and demoralised, and I went to find Mush. He was camping with some others, close to the road. Behind, the mules were calm now, and their eyes shone in the darkness like ebony glass beads. The only light came from lit cigarettes and the occasional torch, and a stiff breeze that made the leaves rustle.

“These Germans are cowards,” I said, my shock turning to rage. “Darn them and their planes. They should face us like men!”

“They are only doing their duty,” Mush replied. “The same as us, brother.”

I disagreed.

“No,” I told him. “They are cowards who drop bombs on civilians. We do not do such things, Mush. We have honour!”

“We follow orders,” he replied. “Just like them. It is the leaders who make the commands. We are merely the spokes on a wheel, brother. It is they who turn it.”

I could not sleep. My mind was filled with blood and screams, and the incessant wailing of Stukas. I rose before dawn and washed my face in a nearby stream. As the cool water refreshed me, I sensed someone nearby. I turned to find Sid Smith, smiling.

“You’re one of the muleteers,” he said. I nodded and told him my name.

“A long way from home, then?”

“Yes,” I replied.

“India?”

“The north,” I told him. “A village, close to Rawalpindi.”

“I’m from London,” he said. “Tooting. Home’s a bit closer for me.”

I splashed more water onto my face and then through my hair. My feet were sore, and my legs seemingly filled with lead, and my head thumped.

“I’ve never been to London,” I told Sid. “I have always wanted to go.”

Sid grinned and the pale skin around his eyes creased.

“Ain’t many like you round my way,” he replied. “Although, I’m not one to hate a man because of his skin. My old man fought at Cable Street.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Oswald Mosely,” said Sid. “He’s a fascist and Nazi-sympathiser. He wanted to march through the East End of London, and the people stopped him at Cable Street. It was a right good punch-up, according to my old man.”

I was shocked. Was Sid saying that a fascist party existed in England?

“But I thought we were fighting against fascists?” I said. “How can there be some in England?”

“Who knows?” Sid replied. “Misguided, wrong-headed? Don’t matter to me. I hate ’em, and I’m happy to fight ’em all, Khan.”

“Me too,” I said. “In India we have people who want to side with the Germans. They want to remove the British.”

“Stands to reason you’d want us gone,” said Sid. “We took your country from you.”

My shock increased. Who was this white man, with his insubordinate views? I had never dreamt that such men could exist in Britain.

“I see your confusion,” said Sid. “I’m a communist, Khan. But this war is about more than politics. It’s about stopping the Germans before they conquer Europe.”

“And communism?” I asked. “I have read much about Russia and Stalin.”

“That’s not my version of communism,” Sid told me. “I just wa

nt a fairer country to go back to. We’re cannon fodder, you and I. Told what to do by rich men who have never seen a battle themselves. It was the same last time, too.”

“The Great War,” I said, nodding.

“Stupid name for a war,” said Sid. “Nothing great about it. It was slaughter, Khan.”

“My grandfather fought here,” I revealed. “Le Bassée, Neuve Chapelle and then the Somme.”

“And he survived?”

I nodded.

“He was lucky,” I replied. “Most of his friends died here. Many have never even been found. It was why I enlisted. After my grandfather passed away…”

“To serve the King?” Sid smirked. “I fight for my people, mate, not some toff in a crown.”

“To help,” I told him. “The Raj is all I have ever known. It is my duty to serve it.”

Sid knelt beside me and began to wash his face.

“Better get moving,” he eventually said. “The Jerries will be back at first light, and no mistake.”

“Jerries?” I asked. Sergeant Buckingham had used the phrase too.

“Nickname for the Germans,” Sid replied. “Although I can think of some other choice words for them!”

We walked back to camp together, to find everyone readying to march on.

“I’ll see you down the road, then,” said Sid.

“It would be a pleasure,” I replied.

“Stay safe, Private Khan.”

4

We continued northwards, via Béthune, and arrived at a town called Cassel two days later. We made for the grounds of a once-grand chateau, now fallen into disrepair, and set up camp. We were great in numbers, and the chateau grounds were not large enough to take us all, so some camped in a field instead. And, once again, we settled and tried to find some kind of normality.

I was hungry and tired but made sure to look after my three mules before taking care of myself. The animals were calm, but seemed sad to me, ridiculous as that may sound. I had learned much about them on our journey, however. Where they might nuzzle and playfully butt each other before, now they were still, their heads drooping. I found a grooming kit and began to remove their blankets and noticed that their coats were dulled and ragged.

“Don’t worry, my friends,” I whispered. “Fazal will see to you.”

One by one, I groomed and cleaned them as best I could. Then I found a hoof pick and checked each of them. The journey had been hard, and I was wary of being kicked by them, so I took my time and found plenty of debris to remove. In India, we had carried field forges with us. These allowed us to re-shoe our mules on the go. But in France, we had not been issued forges, and so their hooves had taken great strain. All three needed shoes, but when I spoke to Sergeant Buckingham, he began to laugh.

“Impossible!” he told me. “Even if we had the shoes, we have no forges, Khan.”

“But without the shoes, the mules will suffer,” I told him.

“We’re all suffering, Khan!” he bellowed. “I haven’t the courage to look at my own feet, lest they be riddled with rot. Forget the beasts, man! We’ve got humans to consider.”

When my face fell, he grew annoyed.

“Don’t tell me you worship the useless things?” he said. “I had enough of cow-worshipping Hindustanis in Delhi!”

“I am a Muslim, sir,” I replied. “We do not worship animals.”

“Glad to hear it!” said Sergeant Buckingham.

I walked away in anger and despair. My mules were not desperate for new shoes, but if they didn’t get them soon, they would find walking painful. And, like cars without wheels, mules with injured hooves were no good to any of us.

“What is the matter?” asked an older comrade called Sadiq.

He was from Rawalpindi like me, tall and strong, and wearing a regulation pagri – a turban – which consisted of cloth wrapped around a quilted cotton cone. When I relayed the Sergeant’s words, Sadiq merely shook his head.

“What can you expect of people who steal other’s countries?” he asked. “They do not care about us, never mind the animals.”

“But the mules are just like us!” I insisted. “We have a duty to them.”

“Nonsense!” Sadiq replied, smoothing his oiled moustache. “We have only one duty, Fazal. To stay alive in this hell.”

“But…”

Sadiq shook his head again.

“Listen, brother,” he said. “We are not alone in feeling this way. Do you believe that the white soldiers feel any differently? We came for victory, and we are running from the fight. Don’t tell me about duty or honour. There is none to be had.”

That night, I rested well. It had been many days since my last real sleep, and when morning came, I was groggy and grumpy. Mush awakened me, and together we walked to the latrines to relieve ourselves. Captain Ashdown was standing nearby, engaged in conversation with Sergeants Buckingham and Davis, and another Captain called Morrow. All four of them wore serious expressions, and their exchange seemed heated.

“I wonder what they are saying?” Mush whispered.

“I can’t hear,” I replied.

“More bad news, no doubt.”

In the mess tent, we were given tea and biscuits, and some bread and jam. I scoffed mine quickly, and took an extra cup of tea, too.

“I am desperate to bathe,” said Mush. “I feel dirty.”

“Me too,” I told him.

“I have not washed for days and my uniform is making me itch.”

“Perhaps we will have time later,” I suggested.

“If the Germans spot us here,” Mush replied, “there will be no later.”

With breakfast done, we headed for our tasks, rested and refreshed, and the sun broke through the clouds to further brighten the day. My mules were tethered close to our tent, and once again I began my grooming routine. They seemed happier and more relaxed after a quiet night, and again I could not help but compare our lots.

“Only, you did not choose this life, Baba,” I told the pale brown one. “You did not choose anything.”

One of the others reared its head and nudged me, and I returned the gesture. To my left, Mush began to laugh.

“They are mules, brother,” he said, “not future wives!”

During late afternoon, I took a stroll around the grounds and found that the chateau was deserted. The main house was derelict, with fire damage to the rear, and fallen stonework. Rats scurried from an outhouse when I tried the door, giving me a fright. Further along, through a courtyard, I found Sergeant Buckingham smoking his pipe and reading a letter. He had removed his jacket and tie and unbuttoned his shirt and had his feet up on one chair as he sat on another. A hip flask of whiskey sat on a small table beside him, and his eyes were glazed.

“What are you doing, Khan?” he asked.

“Nothing, sir,” I replied. “I was just taking a walk.”

“Well, go elsewhere, will you?” he said. “I wanted some peace.”

“Yes, sir,” I replied, before making a hasty exit.

I wandered towards a small copse which led down to the river that ran behind the grounds. The water was clear and fresh, and I sat on the bank and daydreamed. Tranquillity seemed out of place, given our predicament, but it was very welcome. I must have been there a while before I spotted the boy. He stood on the opposite bank, holding a stick to which he’d tied some string. A fishing expedition. He must have been ten or eleven years old, with dark hair and eyes and a sallow complexion, as though he hadn’t eaten enough.

“Excusez-moi,” the child said when he saw me, “je ne voulais pas vous déranger.”

The boy looked scared and unsure of himself. I shrugged and gestured to my mouth.

“I do not speak French,” I told him.

The boy looked past me, and his eyes lit up. I turned to find Captain Ashdown standing behind me.

“He said he didn’t mean to disturb you,” the Captain explained, before turning to the boy. “Vous ne devriez pas être ici.”

The startled boy turned and fled, and I asked the Captain what he had said.

“I told him he shouldn’t be here,” he replied. “We can’t have civilian children running about. There are live weapons around.”

“You speak French?”

“Yes,” he said. “Taught at school.”

“In England?”

Captain Ashdown shook his head.

“No, Khan,” he replied. “In India. I was born and raised there.”

“I did not know that, sir,” I replied. “Please forgive my mistake.”

“At ease, Khan,” the captain said. “There is no mistake to forgive.”

I wondered whether to ask about our situation but decided against it. I was a private, and my orders would come when they were ready. Instead, I asked a more general question.

“How long will we rest here?”

“Not long,” said Captain Ashdown. “I’m awaiting further details from England.”

“The Germans are gaining ground?” I added.

“Yes,” the Captain replied. “The enemy is closing in, Khan, and I think we might be in for a frightful battle.”

“We are here to win,” I said, remembering what Mush had said.

Captain Ashdown sat and smiled.

“Yes,” he said, “but let’s enjoy the peace for a while, shall we?”

I smiled in return and spoke again.

“Permission to bathe in the river, sir?”

The Captain nodded.

“You don’t need my permission for everything,” he told me.

I walked back to fetch Mush and wondered when our next brush with death would occur. We did not have to wait for very long.

5

The next morning, a local farmer arrived with a number of butchered chickens. He spoke with Captain Ashdown for a while, before the two of them shook hands. I was standing with Baba and my other mules, carrying out my chores with Sadiq, and the Captain beckoned to me.

“Monsieur Legrand has given us these chickens, Khan,” he said. “I thought you and your fellows could cook something for yourselves. Something a touch Indian, perhaps?”

I glanced at the chickens and my stomach growled. Unlike most of the Punjabi men I knew, cooking was one of my special skills. In India, I had often helped the cooks in our company. However, the chickens had not been slaughtered in accordance with our religion. They were not halal. Then again, nor was the bully beef we had been eating, and not a single man had complained. Perhaps, in such a perilous situation, we could be forgiven. Our need for a hearty meal was great.

The Royal Rebel

The Royal Rebel Mohinder's War

Mohinder's War Starting Eleven

Starting Eleven Glory!

Glory! (Un)arranged Marriage

(Un)arranged Marriage Tales from India

Tales from India The Night Run

The Night Run Voices: Now or Never

Voices: Now or Never Rani and Sukh

Rani and Sukh Stars!

Stars! Web of Darkness

Web of Darkness The Crew

The Crew Fire City

Fire City The Last Taboo

The Last Taboo